A Trip Back in Time

Imagine the following scenario: The year is 1992. Mrs. Smith has instructed her 10th-grade history class to spend class doing research for an upcoming report on World War II. The construction right outside the window is a slight distraction to most students, but fifteen-year-old Josh cannot concentrate. He hears every whir of the motor of the backhoe, every pounding of the jackhammer breaking through rock, and every single word the construction workers say. Finally, in a fit of rage, he throws his textbook on the floor. Using swear words, he yells at Mrs. Smith that he can’t do the research. He screams, saying that he hates school. Then, he storms out of the room. Mrs. Smith tells him, “Fine. You can march right over to the principal’s office.” She gets on the intercom and tells Principal Roberts to expect Josh in the next few minutes.

Later that week, Mrs. Smith and Principal Roberts have a meeting with Josh’s parents. In 1992, the discussion and outcome of this meeting would have been different than in 2022. They might have depended on individual notions of appropriate behavior for a fifteen-year-old based on educational guidelines at the time, articles in professional journals, and, perhaps, past personal experiences. It is quite possible that while Mrs. Jones and Principal Roberts do not understand why Josh behaved this way. It is a problem that has persisted since elementary school. However, they have some vague idea that it’s not out of maliciousness and that it’s largely beyond his control. Since nobody understands the origins or context of this behavior, the principal, teacher, and Josh’s parents are at a loss for how to manage this situation. More importantly, they don’t know how to help Josh.

A Dark Age of Understanding

That Josh’s teachers would have had some understanding that his actions were unintentional would have been the best possible scenario. Unfortunately, the 1990s were still part of an era in which invisible disabilities and differences were often undiagnosed and misunderstood. Although laws were in place since the 1970s to guarantee appropriate education to students with special needs, many invisible needs were overlooked.

All too often, students like Josh would have spent the afternoon in detention. They were labeled as disrespectful and branded as having a behavior problem. Josh would not have been identified as having an invisible disability. Educators would not have analyzed Josh’s behavior using tools that validated what he experienced in his everyday life. Ultimately, adults and peers would have understood Josh’s outbursts superficially, rather than the manifestation of a differently-wired brain.

Perhaps Josh’s parents would have grounded him and made him write an apology letter to Mrs. Smith. Josh would have tried to explain to his parents that he didn’t mean to have that outburst. In exasperation, they would have told him that at fifteen years old there is no excuse for this behavior. They might have even thought that his actions were the result of conscious choice, not something beyond his control. Josh would have felt shamed by his parents and educators. He may have dreaded going to school out of fear of being taunted by classmates who witnessed the outburst.

“Different” in a More Enlightened Era

Fortunately, the world has drastically changed since 1992. Thirty years later, behaviors like Josh’s are better understood. Today, someone like Josh would likely be diagnosed as autistic in elementary school and identified as having extreme sensory sensitivities. Importantly, adults would understand that punishments for Josh’s behavior would be ineffective. In fact, they would make things worse by shaming him for something that he is unable to control.

Teachers, counselors, and psychologists would be able to contextualize and understand Josh’s behavior. They would have the tools to arrive at a solution to help Josh and his teachers in a classroom situation. This would be done through a Functional Behavior Assessment (FBA). FBAs were established in 1997 to be a fundamental and legally required part of a student’s IEP. They are developed by educators who regularly witness behavior that interferes with classroom dynamics. To create an effective FBA, members of the IEP team need to do the following:

1. Identify the problematic behavior

To identify the problematic behavior, it’s important that educators describe the behavior in concrete terms. For example, a poor way to describe Josh’s behavior is, “Josh doesn’t control his temper.” A concrete way to describe Josh’s actions is, “Josh throws things and uses swear words when overwhelmed by extraneous noise.” The latter describes the context in which the behavior occurs. When there is a great deal of noise, it is overwhelming for someone like Josh who has sensory sensitivities. Additionally, rather than his behavior being labeled as an “outburst”, it would be called a “meltdown”. This is the more acceptable terminology in the autism community for this type of behavior. It differentiates it from willful misbehavior or a childish “temper tantrum.”

2. Determine if the behavior is linked to a skill deficit

It is important to understand whether Josh realizes how his behavior is perceived by others. Is he aware that it is disruptive and inappropriate? Does he appreciate how jarring it would be for him to witness somebody else doing the same thing? Does he know how to control his behavior? In my example, yes, Josh does understand that his meltdown is not a socially-appropriate response to his stress and anxiety. He even feels shame and wishes he knew how to prevent it from happening. The teachers who know him best might even understand that he would behave differently if only given the tools to do so.

3. Tips for conducting the behavior assessment

Please remember that a student with an invisible disability is an individual with agency, not a “problem” to be “solved”. The IEP team must ask Josh questions to help identify the source of his behavior. For example, they might ask Josh how he felt before he threw something and yelled at his teacher. The kind of answers that Josh provides depend on how old he is when information for the FBA is gathered. Hopefully, he will be able to convey that he felt anxious and frustrated.

Teachers should also note what happens after Josh has a meltdown– he usually walks out of the classroom. Rather than being rebellious and disrespectful, Josh is trying to take care of himself. He is extricating himself from an unbearable situation. With the FBA, the IEP team will have an idea of what accommodations to provide to prevent future meltdowns.

In the case of ongoing construction, an obvious solution is to allow Josh to find a quiet place to work. The library or another quiet classroom are good choices. If a teacher is giving a lecture, maybe she should give him the notes to study. She can arrange for some individual time with him to ascertain understanding. If it is not possible to send Josh to another room during a lecture, perhaps the teacher can allow him to walk around the building with a paraprofessional or other qualified support staff for ten minutes in order to decompress.

4. Collecting data

It is important for educators to collect and record data. They may use a graph or scatter plot to record the relationship between certain environmental factors and how Josh responds. For example, after Josh has been given permission to work with a paraprofessional in the library, the graph or scatter plot will indicate that Josh’s meltdowns have been dramatically reduced. Perhaps he had one or two when he became frustrated because he didn’t understand the material. But this is a far cry from the near-daily meltdowns he had when also dealing with the loud noises coming from outside. The relationship between environment and behavior should be clear.

At the next IEP meeting, the educators will discuss with parents the improvement they have seen in Josh’s meltdowns. They will note that these meltdowns are now far less frequent. However, the paraprofessional may have observed that Josh occasionally has a meltdown in the library when he doesn’t understand material. In that case, the IEP will be revised to help Josh address this issue. It could be revised to consolidate material into manageable components and encourage him to highlight something he does not understand. He may engage in discussion with the paraprofessional. He may also be allowed to be physically active for ten minutes in order to relieve stress.

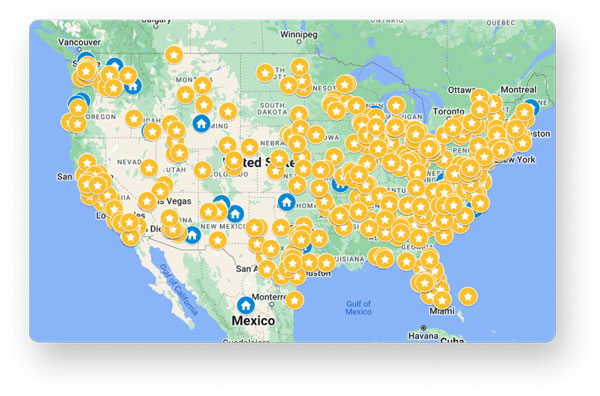

It is crucial to collect data frequently to visualize and report on these changes; while 80% of teachers still collect data on pen and paper, there are many software solutions that can reduce the time burden of data collection. fastIEP is an all-inclusive way to track data, create graphs, and generate automated reports for your students’ goals — and you can try it for free today at go.fastIEP.com.

5. Providing positive feedback to the student

I have noticed that a common complaint among many autistic people who grew up in the ‘90s and earlier is that parents and teachers were quick to point out what they did wrong but rarely commented on what they did right. As someone on the spectrum, I can attest to this. Many autistic people know and understand more than the world gives them credit for. They are often aware that they are being observed and scrutinized. It is important for these kids to know that they are being heard and understood. Adults should learn to appreciate their efforts even if the outcome isn’t always ideal.

For example, Josh’s educators would be wise to say something like, “Josh, I know how difficult it must be to have to hear all that construction going on outside. This is why we let you work in the library. I can see that you’re more relaxed there. You are also trying very hard to prevent meltdowns when you don’t understand the material. You’ve come such a long way this year. I’m proud of you and you should be proud of yourself.”

Even if Josh doesn’t respond overtly to the educators’ positive comments, he definitely hears them and is internalizing them. After all, autistic kids internalize the constant negative feedback they hear. This positive feedback helps them feel validated, understood, and it encourages them to stay motivated.

Just as Josh has an “invisible” need that may often go unnoticed, the strategies of a thoughtful FBA might seem “invisible” at first—until they start to have a positive effect on Josh’s ability to learn in a classroom setting and feel accepted as an individual.